Rob Davis: "How I Wrote a Fork of Books"

30 September 2019

I struggle when people ask me to explain the three books I’ve just written. Everything I have to say about it is in the pages of the books. And do people really want me to explain, or is it just that the books have left them feeling puzzled? Well, that was partly the intention. I mean, hopefully they were delighted and puzzled in equal measure, but I happen to think that feeling puzzled is no bad thing.

With these books, I wanted to create a world that felt bewildering and mundane at the same time. I wanted to tap into the transformative power and mind-numbing boredom of being 15 without resorting to retro-cultural referencing and being confined by familiar story tropes. I wanted a teen landscape that had trauma for furniture and boredom like dynamite, where the familiar was unfamiliar and the fantastic was bland. Because that was how my world was when I was 15.

JG Ballard described the Surrealists as having "created a series of valid external landscapes which have their direct correspondences within our own minds." I don’t know if it makes me a Surrealist, but I wanted to achieve something similar.

I wanted a world where you could be bored out of your mind by knife rain, kitchen gods and knowing the precise day you would die.

So maybe the puzzle that is really puzzling the puzzled is what kind of books these are. Maybe, with the third book in the trilogy about to appear in shops, folk want to know if this is all allegorical, or if it’s a dream, or sci-fi or fantasy... That’s probably a fair question, so I am going to try and answer it. With no guarantees that I’ll bring comfort to the puzzled.

I had grand ambitions of not falling into any genre when I started these books. I doubt I’m the first author who set out with that desire. I did not want to deliver upon expectations. I’m not against having my expectations met by certain entertainments, but I do look to art to confound my expectations and startle me, to engender a sense of wonder so that I can look at the world with fresh eyes.

As a side note, it’s worth pointing out that this is why art and capital don’t mix. People will buy a thing based upon having expectations delivered. We don’t order something through the post without knowing what it will be. And yet how we still yearn for surprise. Selling a book on the premise of not delivering on expectations is difficult, though. And with all due apologies to my publisher for embarking on such an experiment, I would like to add that creating one is also problematic.

One way I sought to navigate the expectations problem, having already created an impossible world, was by making three books that each take the perspective of one of the three main characters and offer three different readings of that impossible world. Then I realised that my three main characters were each representative of a genre. One character represents realism, one character represents fantasy and one character represents science fiction. This idea proved very useful.

1. Realism

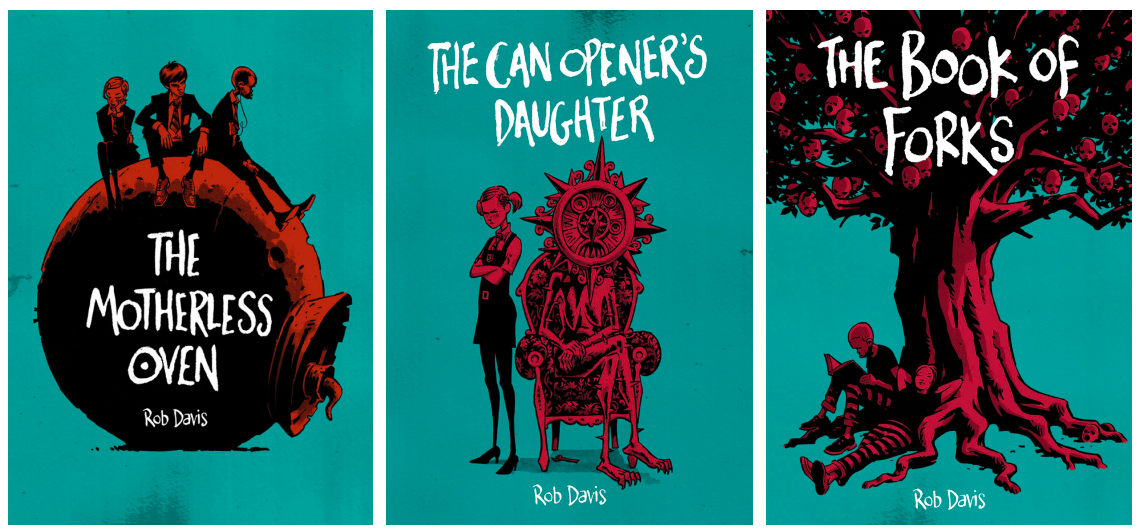

The first book, The Motherless Oven, is told by Scarper Lee via his home gazette (which is like a cross between a diary and a talking vase that’s given to kids when they are soon to die). Scarper has three weeks left to live and is miserable and resigned. What is crucial here, though, is that he is always miserable and resigned. He is resigned to reality. His reality is one where everyone has a deathday and children make parents (rather than the other way round), but because he is resigned to this reality we take that reality as a given.

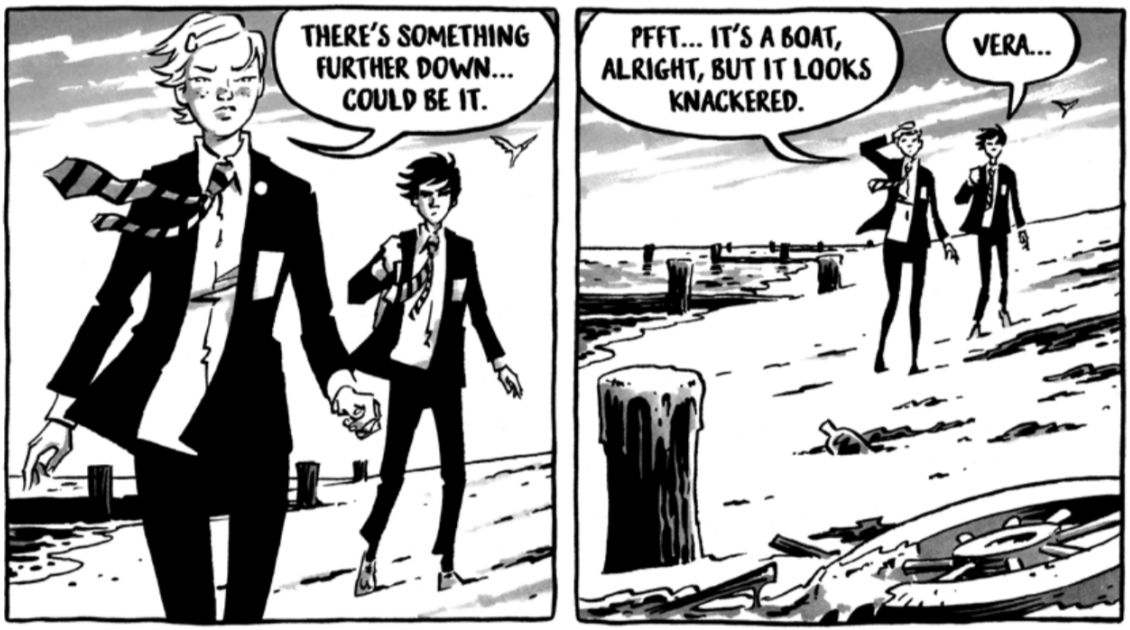

Therefore his story is more like realism than fantasy. Our narrator is not discovering a weird new world (like Alice in Alice in Wonderland). The weird stuff here is mundane to him and so to us. The weirdest thing in his world is the new girl in his class. No one gains magical abilities or powers, no one saves the world or has an epic quest. Christ, they don’t even manage to leave the town they live in. Equally, there are no explanations of this strange reality to offer some rationale for how it relates to our own world, so it doesn’t work as science fiction, either. In a sense, this is alienated-suburban-teen-reality made even more real because what it feels like is wallpapered onto the walls of the world all around us. Scarper Lee is a realist and his book is told like a realist novel.

2. Fantasy

Vera Pike is the fly in the ointment of Scarper’s world. She is that aforementioned weird new girl at school who becomes his enigmatic friend. The first half of the second book, The Can Opener’s Daughter, is narrated by Vera in flashback. Now, something different is happening here. Because Vera is not like Scarper and she is our new narrator, the way we engage with the world shifts. Vera is a fantasy character; she is heroic (or villainous, it’s hard to tell sometimes and the two can be interchangeable) and, of course, heroes are a fantasy. It’s probably worth stressing that - heroes do not exist in real life, and the moment a hero enters any story it is no longer realism. So, as I was saying, Vera’s story is in flashback, because that’s another thing about heroes: they have backstories, creation myths. (Poor old Scarper just had days of the week.) Vera has supernatural aid, thresholds, mentors, she even gets to slay the dragon (her mother) and rescue the damsel-in-distress (a miserable teenage boy in this case).

It’s important to remember that Vera is not a hero or villain outside of her own worldview (and it is that which we are concerned with here). This is because she is an idealist. It is how she sees the world. She believes she can change the world, bend it to her will.

3. Science Fiction

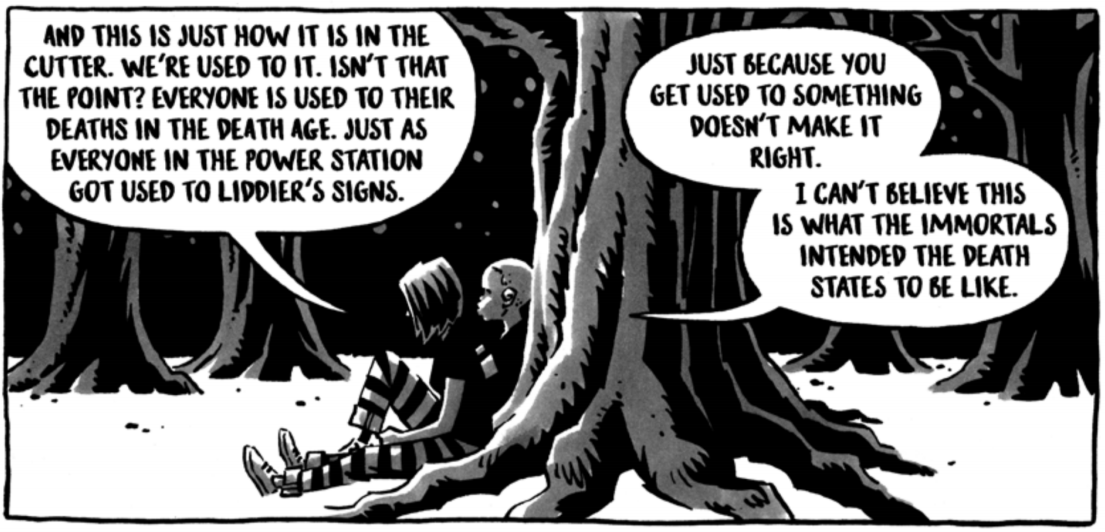

In the third book, The Book of Forks, Castro Smith is our narrator. Previously, he had appeared as an outsider figure, befriended by Scarper and Vera. In the realism of Scarper’s world, he was mentally ill; in the fantasy idealism of Vera’s world, he was a mage-like figure who knew deeper truths about the world. In reality, his outsider-ness gives him an objectivity and his form of mental illness is Inference Syndrome, so he is constantly looking to speculate and make sense of the world, to look for meaning. In this sense, Castro is science fiction. His book will connect the speculative with the science. His narration takes the form of an encyclopaedia he is writing called The Book of Forks that explains everything about the world.

A side note about science fiction. Darko Suvin described science fiction as a form of cognitive estrangement, because it introduces something new to us and its presence compels us to conceive of our world in a new way. Cognitive estrangement is also the best way to describe the ‘illness’ that Castro suffers from and which makes him an outsider in his world.

So The Book of Forks offers the explanations those puzzled readers may or may not have wished for, not because they wished for them (if they did) but because it is Castro’s nature and bound to be his narrative. In explaining how a world could ever exist where children make parents, it rains knives and everybody knows their deathday, the book became a form of science fiction that grew to monstrous proportions and of which I feared I would lose all control. Thankfully, with Castro as cypher, it retained just enough subjective perspective to get it onto paper. And even if it appears to be the explanation of the world, it remains, however convincing it may be, Castro’s explanation of the world.

So, that experiment is over and I can try and heal my splintered mind. It was quite an effort and it may be that the question I could ask myself is, “Why did I bother?”.

I have wondered in my darker moments why I didn’t just look to earn a decent living and retain my sanity working on some franchise or other. The answer I tell myself is that I did these books because I believe in new metaphors. JG Ballard (him again!) talks about the world needing new metaphors and I agree. I’m not a fan of the popular notion in fiction that everything has been done before so therefore don’t look for anything new. A culture that runs on old metaphors is one that is speaking to the past. And the past doesn’t listen. There is a world here right now that demands new metaphors. And the perfect metaphor can launch a new reality into the world.

The third and final volume of Rob Davis's award-winning trilogy, The Book of Forks, is published on 10th October.

Tags: