Jurga Vilė: How I Wrote Siberian Haiku

1 April 2020

Jurga Vilė is the author of Siberian Haiku. Here we spoke to her about the inspiration for the book, her grandfather's journey, and the importance of exile literature.

Hi Jurga, can you explain briefly what Siberian Haiku is about?

Hi Jurga, can you explain briefly what Siberian Haiku is about?

Sure, it’s the story of 8-year-old Algis, who in 1941 was deported with his family to Siberia. That was the destiny of many Lithuanians during the Soviet regime’s occupation. From the very beginning of the long journey, Algis decides to take it as an adventure and to stay positive for as long as he can. His story is a flash-back, which he shares while coming back from the exile. He tells us how everything started, recalls the journey to Siberia, the life far from Lithuania, and finally his return home by Orphan train.

The story is based on your father’s experience - was this something you were aware of early on in life, was it talked about, or something that you found out about later?

When I was little, every now and then dad would mention Siberia to me and my brothers. He would tell us in hushed tones about his family’s deportation. My dad used to tell us the story about frozen potatoes, that he was grateful to find one back there, and how he would have eaten it with pleasure. I pictured Siberia as an ice-cold place far, far away, where people lived with rumbling stomachs and icicles dripping down their noses. When I was little, I could never understand how my father being just a child had ended up in such a horrible place. His past seemed full of secrets.

So when did you find out about his journey?

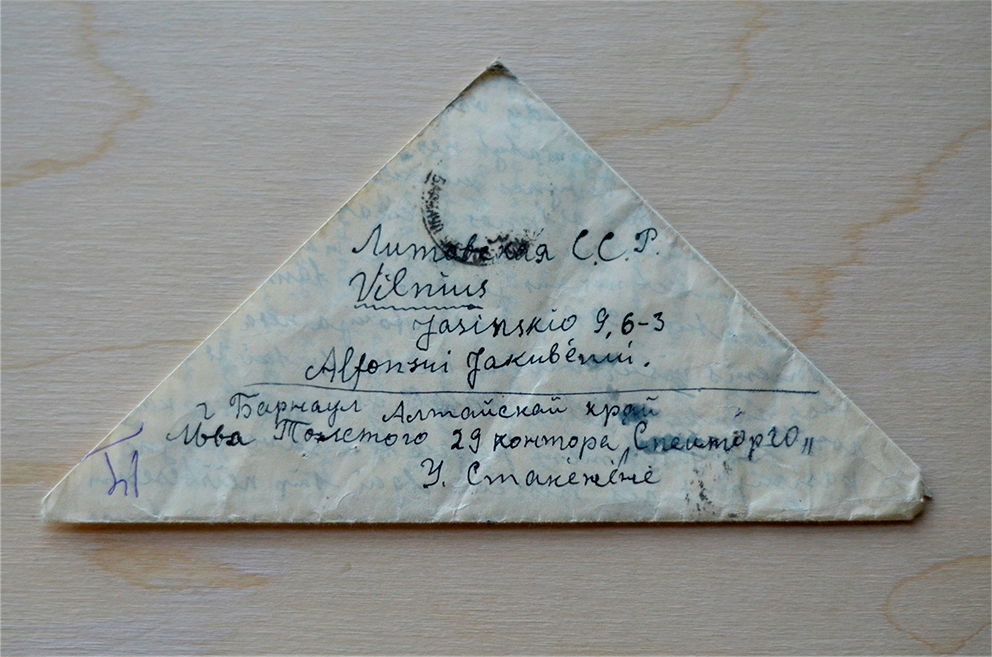

In 1990 Lithuania declared its Independence. I was thirteen and they were thrilling times. Freedom was in the air and we couldn’t breathe without it anymore. The numerous demonstrations, seas of our national yellow-green-red flags, songs and poetry till night, people’s eyes full of hope. The deportees who were lucky enough to return home started publishing their memories. These books were named “Exile Literature”, and I devoured all of them. But my grandmother’s tiny notebook which I discovered at the same time was my favourite. I read it again and again.

Was this the catalyst for writing Siberian Haiku?

My dad‘s mom, my grandmother Ursula, was not very talkative. She was carrying Siberia inside, lots of suffering and trials. She wrote her memories about the exile in a laconic and clear way. She talked about the pain, not forgetting to mention the beautiful Siberian nature and the kindness of people. While reading these almost transparent pages written in pencil, I always felt a tender mist around. It would fall from the past in little salty drops.

I was curious about the feeling it produced to me. A word was fluttering in my mind like a butterfly. When I caught it, I recognised it. It was a feeling of ‘haiku’. That’s how the title of a future book arose naturally: “Siberian haiku”. I wanted my book to be somehow similar to what my granny wrote. When you’re face to the ground and you feel the wings growing. I imagined my book full of light.

Was the plan always to make it a graphic novel?

Well, there were different thoughts and one of them was a script for a film. I tried to enter a scenario writing competition in Paris, and I chose the theme of kids coming home from exile by Orphan train. Then I abandoned that idea. But not the wish to tell the story in my own way. Then I realised that graphic novels are good for approaching difficult subjects, and in Lithuania the idea of graphic novels are quite new, so I thought it would get more attention.

How do you write, do you sit at a desk or go to coffee shops?

I work as a translator, and sometimes I do other little jobs, like working as a cashier in a museum, making cartoon theatre performances or workshops for kids, planting plants... so I write when I can. I write letters almost every day, but most of Siberian Haiku I wrote when I had a chance to get away from my daily routine. So I could concentrate on myself. I never write in coffee shops, I gather information and inspiration in different places, and I write at home or at a place which is home at the moment of being.

How long did Siberian Haiku take to write, were there any challenges?

It’s quite difficult to say. I carried it with me for a long time, many years. Meanwhile it was changing. But finally I imagined it pretty much as it is now. These short chapters, episodes mixing comics technique, collages of letters and blocs of texts. It took me almost a year to write the script.

At what point did Lina get involved, was the script finished when she did, or did you work together on the final story?

The text was written, and I was looking for an illustrator. Funny enough we noticed Lina because of her Japanese surname [Itagaki]. It drew our attention as there’s an important Japanese line in the book, but it was a predestined meeting. For both of us Siberian Haiku is a debut, and we were eager to devote ourselves to the project absolutely. Lina felt the story, dove into it and gave life to it with her very subtle drawings. She also rewrote the text by hand, which reinforces the impression of reading a little boy’s diary.

What was it like working with Lina, what did she add to the story?

As I didn’t know who was going to illustrate the book, I wrote it with the precise indications to the illustrator. I agree that it’s quite awful for illustrators to get this kind of script, it was my first time and I didn’t know. But Lina liked it, she said it helped her a lot. And I was encouraging her to interpret my notes as she saw fit. We worked, separated by distance. At that time I lived in Andalusia, Lina lived in a Lithuanian port Klaipeda. We were exchanging emails a lot, sometimes talking on Skype.

Lina is very precise and hard-working, and I also liked her decision to choose quite a realistic way of illustrating. She consulted lots of photos, worked with archive materials. We actually got to know each other after the book was published. We met for the first interview about Siberian Haiku, and then we went to a cafeteria to talk and get to know each other better.

Lina is very precise and hard-working, and I also liked her decision to choose quite a realistic way of illustrating. She consulted lots of photos, worked with archive materials. We actually got to know each other after the book was published. We met for the first interview about Siberian Haiku, and then we went to a cafeteria to talk and get to know each other better.

How important is Siberian Haiku as a piece of personal and cultural history?

Siberian Haiku is a personal story, but inseparable from the historical context. It permits me to recount an important moment of my country’s history. It’s true, that the culture’s involved a lot, too. You can actually learn a bit about Lithuania reading Siberian Haiku, you can smell it and taste it, imagine its nature, hear its songs. But the main theme of the book, I think, is humanism. An innocent kid deported from his home and growing up in a cold Siberian land for me echoes like a refugee’s stories. It’s true that nowadays people often migrate by their own will, but others are still forced to leave home.

Siberian Haiku is available now.

Siberian Haiku is available now.

Tags: